Ada led a strong and remarkable life. While alive she was occasionally called "the brainiest woman in New Mexico!" Ada had strong opinions and passions for her causes...which were many. She often delivered persuasive speeches on behalf of those causes, especially her vehement anti-alcohol advocacy. Likewise, Ada was a voluminous writer of letters to the editors and politicians of her era. How and where did Ada become such a capable orator, writer and proponent of social causes?

It all started when Ada McPherson was born on August 26, 1852, in Winterset, Iowa, to Marquis Lafayette and Mary E. Tibbies McPherson. Although we have found nothing (yet) about her childhood, Ada's father set the stage, tone and tenor of her life.

As a youth McPherson was tutored and mentored by a highly educated Englishman named Preston. He attended Indiana's Asbury University and became a lawyer, eventually settling in Winterset, Iowa, in 1850 where his law firm's reputation spread throughout Iowa. He had an unusual vocabulary, his pronunciation was good, and his reading had been extensive, particularly in history and in the literature of oratory, both ancient and modern. His powers of wit and humor, of sarcasm and invective and denunciation as well as of declamation and reasoning and his universally high repute enabled him to hold his own, even in counties where he was largely a stranger. McPherson was a man of the highest principles and was an uncompromising enemy of evil in all forms. He had a bitter hatred of saloons and the liquor traffic and delivered temperance addresses in the villages and at the country settlements in Madison and adjoining counties while living in Winterset. McPherson was elected twice to the Iowa State Senate serving eight years. He was one of the leaders in securing legislation which gave a married woman the right to own property, to make contracts, to sue and be sued, and which gave her the same right in her husband's property as the husband had in the wife's property at death. The legislation then adopted with reference to the rights of women has remained upon the statute books until the present day.

After reading about Ada's father, it's easy to understand why she enrolled in the State University of Iowa, the first public university in the U.S. to admit women. Judging from her father's background, it's reasonable to presume Ada received a top notch early education and was instilled with her father's values, behaviors, beliefs and abilities.

|

| Engraving shows State University of Iowa in the 1860's. It is now known as The University of Iowa. |

Ada and Morley must have quickly fallen in love during their time at State University of Iowa. Morley left the school in 1869 to begin his illustrious railroad engineering career. Ada remained in her studies presumably until she received an 1872 degree in English Literature. She and Morley were married shortly after her graduation.

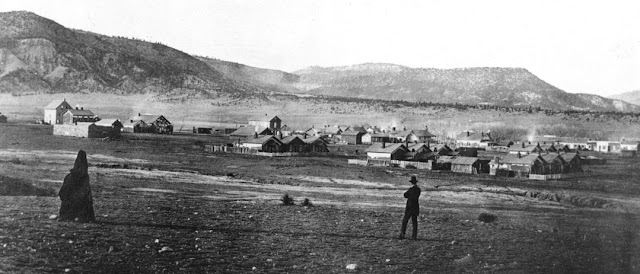

After the wedding Ada and her new husband set forth to Cimarron, New Mexico, a largely lawless little hamlet of about 300 people, to take up residence in the old Lucien Maxwell adobe mansion. W.R. was chief engineer and general manager of the 1.7-million acre Maxwell Land Grant.

Somehow, someway at sometime, W.R. and his bride Ada ran afoul of the infamous Santa Fe Ring. Details are dubious but the upshot seems to be that W.R. and Ada founded a small newspaper and began a purported campaign against the Ring. Ada eventually got in some hot legal water while supposedly attempting to retrieve a letter critical of Catron. Ada's grandson Norman Cleaveland goes so far as to say the Ring put out a contract to kill W.R. The plotline of the Morley Family's Life & Times in Cimarron is murky and seems overly reliant on hearsay, sketchy stories and even some tall tales.

Three certifiable facts of The Morleys Time in Cimarron are that Agnes, Ray and Loraine were born there in the old Maxwell mansion.

After W.R. was killed by an accidental rifle discharge, Ada was temporarily cast adrift. She was surrounded by people trying to tell her what to do. One smooth talking southerern charmed Ada into marriage and convinced her to invest heavily in the cattle business. He rather quickly abandoned The Morley Family but Ada carried his last name "Jarrett" well into her later years.

Ada's happenstance metamorphosis into "ranch woman" is documented in "No Life for a Lady" and need not be repeated here. Agnes Morley Cleaveland wrote the book in the late 1930's with at least 50 years of hindsight to evaluate those times of change for The Morley Family.

After studying other available information sources about Ada, we feel Agnes gave rather short shrift to her Mother. Glancing mentions are given to Ada's many causes and passions. Ada had a busy and complex life away from the Datil Mountains. Her name appears in various newspapers hundreds of times. She spoke far and wide and wrote hundreds, if not thousands, of letters to various editors and politicians. Her upbringing undoubtedly influenced her active role in the WCTU. Ada is also given credit for starting a New Mexico chapter of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Ada spent years working for women's rights and suffrage. She put herself out on the very forefront of those efforts, earning respect far and wide for her unstinting persistence.

Sometime around 1905, plus or minus, Ada went blind and remained largely blind for the rest of her life. Of course, being blind didn't stop her from pursuing her causes, writing her letters and even speaking here and there now and then.

Luckily, today there exists a New Mexico "Official Scenic Historic Marker" honoring Ada's Memory.

We hope someday a professional historian chooses to tackle The Life & Times of Ada McPherson Morley. She certainly deserves more than the fragmentary sources have afforded her over the past 105 years since her passing.

Here's Ada's Wiki:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ada_McPherson_Morley

Note that the Wiki has several factual errors and editorializes on some of the information presented.

No comments:

Post a Comment